Author

2017 International Fellows

Carlos Zamarripa Aguirre, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General of Guanajuato, Mexico; Catherine Ford, State Advocate, Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions: Western Cape, National Prosecuting Authority of South Africa, South Africa; Kirsta Leeburg Melton, Deputy Criminal Chief, Human Trafficking and Transnational/Organized Crime Section, Office of the Attorney General, Texas; Linda Monroe, Assistant Chief, Juvenile Section, Office of the Attorney General, District of Columbia; Ezmarai Osmany, Advisor, Office of the Minister of Justice, Afghanistan; Carolina Barrio Peña, Prosecutor, Delegate for the International Cooperation Unit, Migrant Issues Unit and Trafficking in Human Beings Unit, Santa Cruz de Tenerife Prosecutor’s Office, Canary Islands, Spain.

This group was asked to consider and discuss the various motivators that contribute to illicit criminal activity involving illegal trade practices and the impact this activity has globally on economic and societal health and safety and effective methodologies to address these issues, including consideration on how greed, poverty, opportunity, and demand contribute to the illegal trade of persons and goods.

One of the realities that law enforcement and governmental bodies around the world face when dealing with the complexities of the illegal trade in goods, drugs and people is the seemingly endless supply of would-be sellers, users, and victims. Even successful law enforcement actions that result in the arrest and incarceration of multiple offenders and the rescue of victims fail in the ultimate termination of the activity. New leadership, new victim pools, and new users take the place of the old in a hydra-like manner.

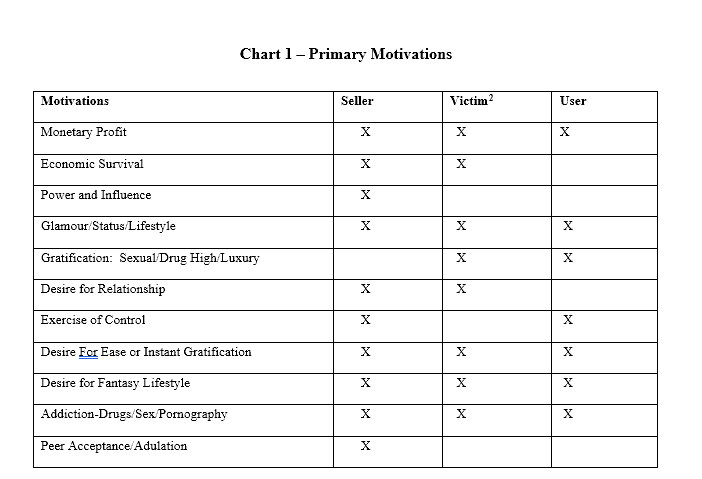

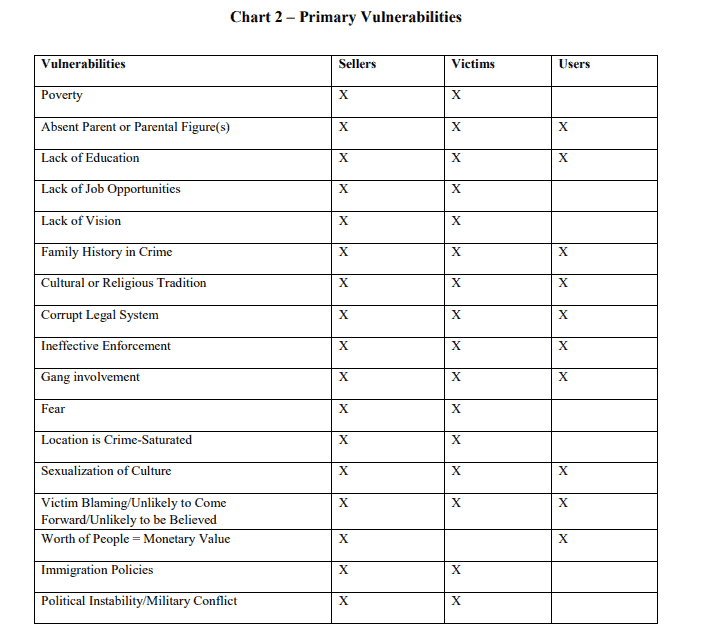

For policy recommendations to be effective, they will need to address both the motivations as well as the vulnerabilities that spur individuals to take their respective places in the marketplace of supply and demand. We have defined motivations as “pull factors,” which are enticements that lead actors toward a specific course of action resulting from the actor’s desire to attain certain goals or status. Vulnerabilities, on the other hand, have been defined as “push factors” involving familial, community, societal or cultural influences that may unconsciously drive actors to engage in or become victims of the illegal conduct.

Motivations/Vulnerabilities

As with most human action, legal or otherwise, people are rarely motivated by a single overriding purpose. The same is true of vulnerabilities. In addition, the same motivations and vulnerabilities often produce both predators and prey.

As prosecutors from four continents, with combined legal experience of more than 100 years, the victims and sellers we have observed, prosecuted, and/or personally worked with often come from similar circumstances in many of the same neighborhoods and are often looking for the same benefits. They both seek to satisfy those desires through illegal conduct and often end up as the exploiters or the exploited on either side of the transaction. As an additional complication, it is not uncommon for sellers to also be users of their own products (including people) or for victims of crimes, such as human trafficking, to exploit and traffic others as they move up the ranks. These complicated actions traffickers and those who are trafficked further blur the lines among these categories of people. Future policies must deal with the fundamental reasons that drive sellers to sell, victims to be exploited, and users to purchase if we desire to move beyond the “they act and we react” method of law enforcement.

While examination and full understanding of the personal motivations and circumstances for each individual who may partake in criminal activity or one who has become a victim would be impossible, some of the more common motivations and vulnerabilities drawing individuals into the illegal trade in goods, drugs, and people are summarized below in two separate charts. Within the charts, each designated group is identified. “Sellers” refer to individuals selling drugs, counterfeit or illegally obtained goods, or people for sex or labor. “Victims” refer to individuals who are exploited for sex or labor or to innocent third party purchasers of illegally obtained or counterfeit goods. 1 “Users” refer to people purposefully buying drugs, counterfeit or illegally obtained goods, or people for sex or labor.

In chart 1, we identify the most striking motivations we determined affect the illegal trade of persons and goods and note where we think, in particular, that sellers, victims, and users are most motivated to participate in illegal activity, either consciously or unconsciously. In chart 2, we identify the special vulnerabilities for sellers, victims, and users we think contribute significantly to helping the illegal trade industry to blossom.

Chart 1

Chart 2

Societal Impact

Volumes have been written about the societal impact that illegal trade in goods, drugs and people have on societies and economies. All three crimes can result in death, for example, 5 from defective air bags, ineffective medication, drug overdoses, exhaustion, starvation, chronic untreated disease, beatings, and murder. All three thrive in and help deplete already weakened law enforcement environments, and make them vulnerable to bribery, contract killings and government officials who willfully choose to benefit themselves or who do so to protect the ones they love.

All three parasitically syphon life and capital from a legitimate economic system and redirect those funds into the pockets of the uber-wealthy criminal minority, as well as funnel proceeds back into continued illegal conduct. All three carry with them a cloud of secondary and tertiary effects that encompass every aspect of violence, intimidation, fear, and community blight. Finally, all three reduce human life to a commodity, equivalent to the profit a criminal makes on a defective electrical cord, the premium produced by addicting children to drugs at an early age, or the money generated from selling people over the internet classifieds like a used sofa or electronic gadget. This normalization of treating people as disposable carries implications far beyond the scope of this paper and tears at the heart of every nation’s stated commitment to the dignity of human life and our international commitment to human rights.

Suggested Methodologies for Addressing the Issues

The recommendations suggested below are intended to serve as broad principles that should be applied across international boundaries and regimes. Successful implementation of these principles, however, will require their tailoring and adaptation at the country and local jurisdictional levels. We were asked this week to “think globally,” but when we return home, we will need to “act locally” as newly informed individuals and in consideration of the experience and insight of our international colleagues. We recognize that these suggestions only cover a 6 small spectrum, but we believe they serve as foundational principles that will help to make a difference if there is political and social will to carry them out effectively.

At the conclusion of this paper, we provided a graphic summarizing the social impact and motivating factors and vulnerabilities associated with the illegal trade of persons and goods and various methodologies aimed at combatting the problem.³

- In certain nations, it remains necessary to develop nation specific statutory law that criminalizes the illegal trade in goods, drugs, and people and obligates and equips law enforcement to investigate and prosecute such crimes.

- Encourage and mandate inter-agency law enforcement and prosecution cooperation within nations.

- Encourage and mandate inter-agency law enforcement and prosecution cooperation among nations.

- Law enforcement investigations should be more proactive than reactive because victims of illegal trade in human trafficking rarely self-identify.

- Law enforcement should be given specific training concerning the investigation of complex cases and the identification of victims.

- Law enforcement and prosecution at senior executive levels must actively encourage and incentivize long-term investigations through policy and staffing choices rather than the accumulation of short-term statistics.

- Prosecutors should work on cases with investigators from the beginning to the end rather than receiving cases that law enforcement has deemed fully investigated, completed, and ready for prosecution.

- Crime specific training should be required for customs, visa, and embassy officials to provide an additional obstacle for international transactions.

- Crime specific education and training for government, law enforcement (both detectives and intelligence) and other professionals, such as doctors, family attorneys, and teachers is necessary.

- Mandatory human trafficking specific education for vulnerable populations including school-age children and parents should be developed.

- Public awareness campaigns are still important and highly relevant to continue educating the public on trends, including discussion on the interconnectedness of illegal trade in goods, drugs and people and the risk factors and societal impacts of each. The public must be kept abreast of the danger inherent in counterfeit goods, the disregard for health and safety laws, the use of slave labor, and the direct link between buying counterfeit goods and organized crime.

- Implement an active and comprehensive asset forfeiture regime at the local, state, or national level.

- Fully fund and staff regulators who create obstacles for the illicit use of the financial system.

- Create memoranda of understanding with financial intelligence units so that reporting reaches both relevant state and federal law enforcement and prosecution with the aim of creating redundancy within the system to recognize patterns and disrupt networks.

- Increase penalties and attach sex offender registration to sex trafficking offenses.

- Provide alternative code provisions that allow for significant penalties for component crimes such as the counterfeit labels that do not have intrinsic value themselves, but are necessary for the success of the overall organized crime scheme.

- Incentivize evidence-based prosecutions that do not require victim-based testimony to prove the elements of the offense.

- Modernize technology for law enforcement, intelligence, and prosecution communities.

- Negotiate and enter into agreements or treaties that require social media, internet service providers, and communications companies to respond to international requests where evidence of probable cause is met and the requested information is related to an investigation or prosecution of a crime in the requesting country.

- Require companies with more than 50 employees to certify yearly that their supply chains are free of human and labor trafficking. Every three years, the company should be required to submit to an external audit to verify the certification. Failure to maintain a human trafficking free supply chain should open the company to civil law suits and potential criminal penalties.

Conclusion

While we have learned a great deal in the past few days of the program about the similarities involving criminal motivations and methodologies in the world of illegal trade in goods, drugs and people, we note as a group that we believe trading in humans is altogether 8 different from the other forms of trafficking. Slavery, in whatever guise, is first and foremost a crime against humanity. Trading in humans degrades the rule of law in a way that the other types of illegal trade do not because it challenges the fundamental value of human life, the basic premise from which all human rights flow.

If a human being is nothing more than a good who can be bought, sold, and disposed of when exhausted, then why should he or she have any more rights than the garments, fishing catch or crops that they are laboring to produce? As we correctly look to analyze illegal trade in all of its facets, we must always remain conscious of the fact that people are different. The trafficker may treat humans like commodities as products to be purchased over the internet for sex buyers or imprison them in a labor camp setting, humans should never be viewed in this belittling way by those whose job it is to protect their freedom, seek justice on their behalf, and provide a voice for them when their own has been stolen. We have accepted that mantle of responsibility and ask that anyone who has a responsibility and the ability to make a difference— no matter how small—to do the same.

¹ It is important to note that while our group acknowledges there are ancillary victims of drug crime, such as people living in neighborhoods plagued by drug related violence, relatives of users who overdose, people from whom users steal, etc., the group opted to spend its attention on a different subset within the population, deeming the other above-referenced persons to not be as pertinent to the discussion involving factors that lead sellers, victims, and users into the relevant criminal conduct of human trafficking, illegal property crimes, and drug trafficking.

² When we refer to the term motivation in relation to victims, we are not blaming victims. We do not believe that anyone offers to make themselves a slave of illegal trade. The motivating or risk factors for victims can better be described as basic needs or desires for things, like relationship or economic survival, which are then used by traffickers to obtain, maintain, manipulate, and exploit the trafficked person.

³ The graphic contained in this paper was created by Carlos Zamarripa Aguirre, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General of Guanajuato, Mexico. The photographs in the background of the graphic also belong to Attorney General Aguirre.