Author

The use of technology in the courtroom has gained acceptance in both federal and state courts with some courts being so technologically advanced that they include annotation and witness monitors, evidence cameras, and integrated controllers.1 Prosecutors practicing in such courtrooms must be adept at using these technologies in order to provide the most competent advocacy for their clients and to be in compliance with ethical standards. Comment 8 to Rule 1.1 of the ABA’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct states: “To maintain the requisite knowledge and skill, a lawyer should keep abreast of changes in the law and its practice, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology, engage in continuing study and education and comply with all continuing legal education requirements to which the lawyer is subject.”2

With the advent of technological advances, prosecutors have increasingly turned to the use of PowerPoints, especially in closing arguments to summarize the evidence and persuade the jury to return a guilty verdict. Recently, in appellate cases, courts have found prosecutorial misconduct in the use of particular images in PowerPoints. A review of some of these cases may help inform prosecutors of the care they must take in designing PowerPoints to use in a criminal prosecution.

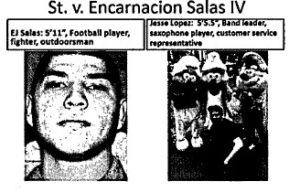

In the latest decision from Washington, State v. Salas, the court found that the PowerPoints were used to inflame prejudice and impermissibly express the prosecutor’s opinion.3 In that case, Encarnacion Salas was charged with the second degree murder of an individual who was described in court as Salas’s good friend. Acquaintances considered them “a couple,” but evidence suggested that, although the deceased, Jesus (Jesse) Lopez, was interested in a homosexual relationship, Salas had not yet agreed. On the night of Lopez’s death, Salas had a knife he routinely carried in his backpack when he visited Lopez’s apartment, which the decedent shared with his mother. According to Salas, the pair went out on a balcony to smoke when Lopez attempted to grab Salas’s crotch. After Salas yelled at him, Lopez attacked him with Salas’s own knife. A physical altercation ensued, with Lopez ending up with 15 knife wounds and dying on the kitchen floor. Salas claimed self defense.

At closing, the prosecutor displayed a 22-slide PowerPoint presentation, which had not been previously shared with the court or with the defendant’s counsel. The first slide contained two pictures. The picture on the right was a picture of Lopez at an amusement park. He was photographed crouched down in front of three characters dressed as Smurfs. A caption about the photo reads, “Jesse Lopez: 5’5.5”, Band leader, saxophone player, customer service representative.” The second picture is an unsmiling picture of Salas from his driver’s license. It is captioned “EJ Salas: 5’11”, Football player, fighter, outdoorsman.” The prosecutor then sought to defeat the self defense claim by highlighting the differences between the physical capabilities of the defendant and the deceased.

On appeal, the defense cited previous decisions by Washington courts4 on the use of PowerPoints by prosecutors, arguing that these decisions required the court to find prosecutorial misconduct. Defense counsel asserted that the PowerPoints at issue communicated to the jury what the prosecutor could not say aloud: that, because Salas was, by nature, aggressive, and intimidating and Lopez was childlike and submissive, Salas had no reason to fear Lopez.

In the previous Washington court decisions, the prosecutors had displayed PowerPoints of photos of the defendants with captions, such as “Do you believe him?” and “Guilty.”5 In State v. Walker, the picture of the defendant’s booking photo was superimposed in bold red letters with the words “GUILTY BEYOND A REASONABLE DOUBT” and 100 of the 250 slides used were headed with the words “DEFENDANT WALKER GUILTY OF PREMEDITATED MURDER.”6

In the Salas case, the court acknowledged that the PowerPoints used by the prosecutor were not as egregious as those used in Walker and earlier cases. The court also acknowledged that the physical difference in size between Salas and Lopez was legally relevant. Nonetheless, the attempt to evoke stereotypes to influence the jury was deemed to be prosecutorial misconduct.

Courts in other states have also found prosecutorial misconduct in the use of PowerPoints. In the Missouri case of State v. Walter,7 the court held that the act of digitally imposing the word “GUILTY” across the mugshot of the defendant was prejudicial. In Ohio, in State v. Mercer, the court reviewed the trial court’s decision in a case in which the defendant was on trial for the rape of a child and gross imposition of a child younger than 13 years old.8 In summarizing the state’s case, the prosecutor displayed a slide depicting a block-form man with horns holding the hand of a block-form little girl. The court agreed with the defendant that depicting the defendant as the devil was “egregious” and flagrantly overstepped “the bounds of professionalism and decorum.”

Other courts have found prosecutorial misconduct because the PowerPoint presentation conveyed improper legal concepts or instructions to the jury. This was the situation in the Oregon case of State v. Reineke.9 The court found that the prosecutor’s slide presentation constituted a comment upon the defendant’s constitutional right to remain silent. Similarly, in the California case of People v. Clark,10 the court determined that the prosecutor presented erroneous information to the jury on the concept of “reasonable doubt” in the PowerPoint presentation used in the closing argument.

Once finding prosecutorial misconduct in PowerPoint presentations, the majority of courts have overturned the defendant’s conviction. However, this is not always the case. For instance, despite the Mercer court’s comment that the prosecutor’s misconduct “would normally result in reversal of the conviction,” the court nevertheless determined that the overwhelming evidence of guilt, the court’s curative instruction directing the jury to disregard the slide, and Mercer’s confession which comported with the testimonial and physical evidence were sufficient to conclude that the trial court did not abuse its discretion in denying the motion for a mistrial on the grounds of prosecutorial misconduct. In contrast, in Salas and Walker, the courts held that the prosecutorial misconduct required overturning the convictions. The Walker court concluded:

Closing argument . . . does not give a prosecutor the right to present altered versions of admitted evidence to support the State’s theory of the case, to present derogatory depictions of the defendant, or to express personal opinions on the defendant’s guilt.11

The Missouri court in Walter overturned the conviction of the defendant despite acknowledging that the verdict was otherwise reasonable because the use of the altered photograph with “GUILTY” on the defendant’s mugshot impinged upon the presumption of innocence and fairness of the fact-finding process.12

Rule 3.4(e) of the Model Rules states that in a trial, a lawyer shall not:

Allude to any matter that the lawyer does not reasonably believe is relevant or that will not be supported by admissible evidence, assert personal knowledge of facts in issue except when testifying as a witness, or state a personal opinion as to the justness of a cause, the credibility of a witness, the culpability of a civil litigant or innocence of an accused.13

The Comment to Rule 3.8, Special Responsibilities of a Prosecutor,14 reminds prosecutors that they have the responsibility of a minister of justice and not simply that of an advocate. While lawyers are reminded in the preamble to the Rules that they can be zealous advocates, the primary duty of a prosecutor is always to seek justice and act fairly and impartially. Finally, the American Bar Association Prosecution Function Standard 3-6.8(a) clearly delineates the permissible contours of a closing argument.15

With these court decisions in mind and the professional standards guiding prosecutors, advocates should ensure that the PowerPoints they prepare:

- Contain only images that have been admitted into evidence during the trial;

- Contain unaltered images;

- Provide information which merely summarizes evidence presented;

- Do not demonstrate the prosecutor’s personal opinion;

- Do not have language that obviates the presumption of innocence; and

- Do not misstate the applicable law.16

No prosecutor wants to diligently and zealously prepare for trial and obtain a guilty verdict only to have that verdict overturned on appeal because of prosecutorial misconduct. As a minister of justice, the prosecutor’s duty is to seek and achieve justice, not merely to convict. As the Supreme Court commented in Berger v. United States,

[The prosecutor] may prosecute with earnestness and vigor — indeed, he should do so. But, while he may strike hard blows, he is not at liberty to strike foul ones. It is as much his duty to refrain from improper methods calculated to produce a wrongful conviction as it is to use every legitimate means to bring about a just one.17

Proper preparation and use of PowerPoint images will ensure that prosecutors can try cases vigorously yet obtain convictions fairly.

Author’s Note: Thank you to Judy Zeprun Kalman with the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office, and NAGTRI Editorial Advisory Board member, for her assistance in writing this column.

Endnotes

- See Herbert Dixon, The Evolution of a High-Technology Courtroom, https://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/tech/id/769/.

- See https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_

of_professional_conduct/rule_1_1_competence/comment_on_rule_1_1.html (emphasis added). - 408 P.3d 383 (Wash. Ct. App. 2018).

- State v. Walker, 341 P.3d 976 (Wash. 2015): State v. Hecht, 319 P.3d 836 (Wash. Ct. App. 2014); In re Pers. Restraint of Glassman, 286 P.3d 673 (Wash. 2012).

- Hecht, 319 P.3d at 841.

- Walker, 341 P.3d at 985. The court’s decision contains some of the images discussed.

- 479 S.W.3d 118 (Mo. 2016).

- 2103 Ohio App. LEXIS 1414.

- 337 P.3d 941 (Or. Ct. App. 2014).

- No. B226624, 2011 Cal. App. Unpub. LEXIS 6763, modified on den. of reh’g (Sept. 28, 2011).

- Walker, 341 P.3d at 991.

- Walter, 479 S.W.3d at 128.

- See https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_

of_professional_conduct/rule_3_4_fairness_to_opposing_party_counsel.html. - See https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_

of_professional_conduct/rule_3_4_fairness_to_opposing_party_counsel/comment_on_rule_3_4.html. - See https://www.americanbar.org/groups/criminal_justice/standards/

ProsecutionFunctionFourthEdition.html. - For a more complete discussion of the use of PowerPoints by prosecutors and a list of cases that have dealt with this issue, see 28 A.L.R. 7th 3. Prosecutors may also want to review the information provided in Ann Brenden and John Goodhue, Persuasive Computer Presentations (ABA 2001).

- 295 U.S. 78, 88 (1935).